Pandolfi: Complete Violin Sonatas

Just as I credit Andrew Manze (as part of Romanesca) for introducing me to Heinrich Biber, I credit him and his former musical partner Richard Egarr for introducing me to the music of Pandolfi-Mealli. It was his second recording, after making a less complete album with Richard Egarr and Fred Jacobs.

In this rendition by Il Rosario, headlined by violinist Daniel Sepec, they present a “complete” collection, lasting 94 minutes total. Sepec is joined by early music specialists Hille Perl, her husband, Lee Santana, and Michael Behringer. For this recording, Sepec borrows a 1680 Stainer instrument, which seems appropriate, given the Pandolfi’s background in Stainer’s circle.

Pandolfi was born in Montepulciano (1624), famous today for its wine. It’s believed he became a priest at some point, changing his name (the score of the op. 3 collection would suggest his acknowledges his birth name, Domenico, and added Giovanni Battista as his religious identity). Colorful in his biography is the murder of a castrato named Giovanni Marquett, for whom he’d already named a musical work. He seemingly did not face repercussions for the act. The music for solo violin and continuo on this album are each clear examples of the stylus phantasticus with quick changes in emotional affect. These changes are differentiated by tempo changes; a change in how we feel the pulse, and in the presentation of new musical sequences given to the violin (and basso continuo).

I found all together Il Rosario’s approach to be different enough from the aforementioned Manze album, but clearly more mainstream in approach than the two-release set from Gunar Letzbor.

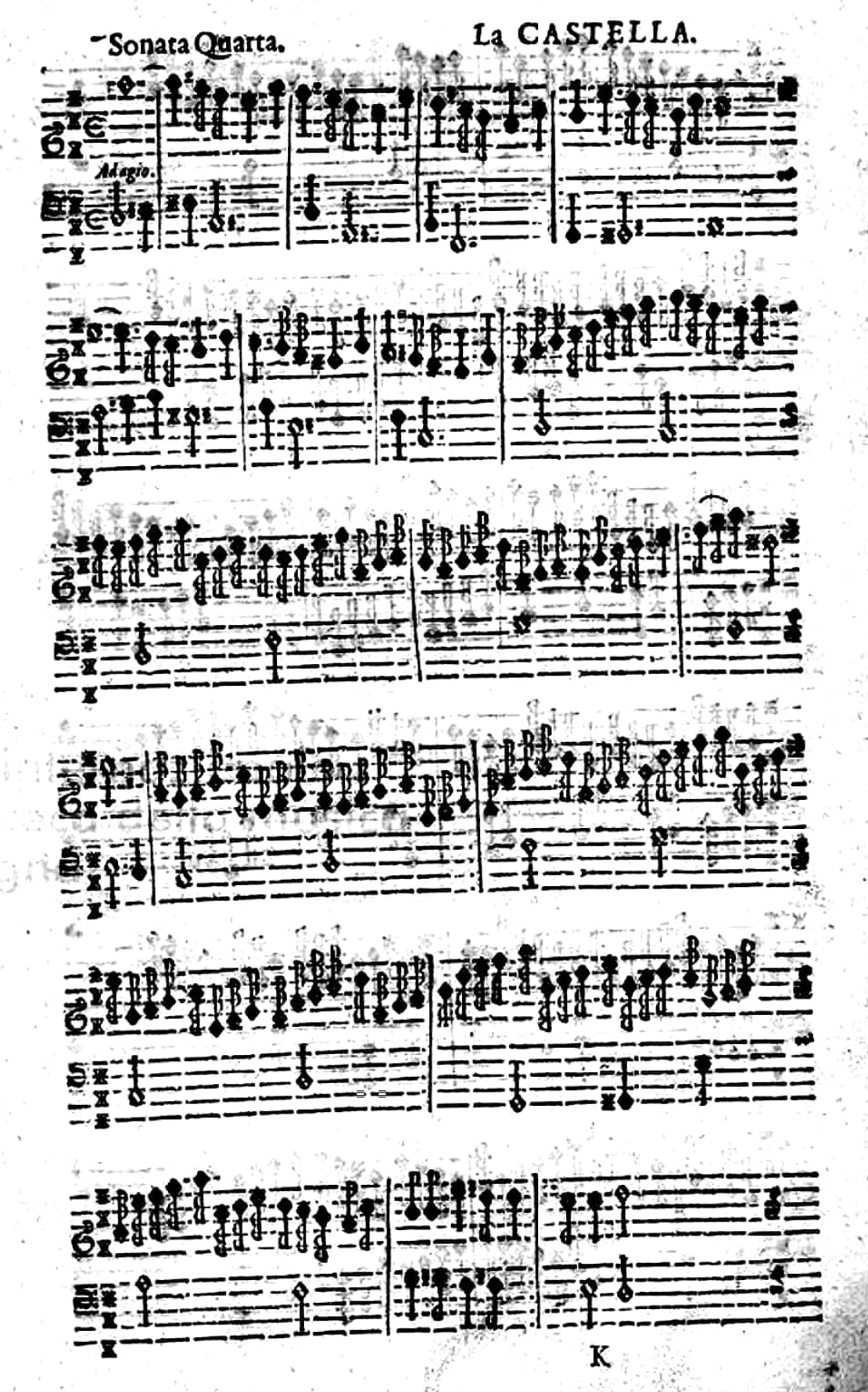

Of interest to me in this music is how violinists either improvise or ornament this music, which is most easily done at cadence points. The original printed edition, done in the Petrucci-style, using a movable type style notation system (versus what would emerge as superior, later, with etched plates created with oiling paper manuscripts) does not provide us a lot of information on how to ornament. I’m ignorant to how musicians may call the style employed here by Sepec, which for me I’d label as “early Italian vocal style” which is an altogether different vocabulary from the types of ornamentation that might have been used by, say, François Couperin later in France, or by Bach in Germany. Some of these effects are include repeated notes or sighing figures (trillo). My guess is that these types of ornamentation were codified in a treatise and that Sepec, like other violinists tackling this repertoire, have adapted to Pandoli’s music, given the period for which it was written.

La Castella, op. 3

This collection was printed in Austria, after Pandolfi had moved to Innsbruck. This sonata is among the most recognizable for me. It’s simplicity is attractive, in how the melodic line given to the violin could live upon its own, or even combined with lyrics. The device Pandolfi uses, which we call a sequence, is a repetition of the same material at different starting pitches. It’s a technique that may seem simple here, but gets carried throughout the baroque as compositional technique.

Sepec doesn’t go too far in the departments of ornamentation and improvisation, however he is flexible with time in the opening, which I think is the most natural place to play with rubato. The support from Behringer at the beginning is nice, moving well-beyond the simple single notes provided in the bass. This piece reminds me that musicians sometimes had to impress their audiences; there are opportunities for the violinist to showcase their skills once the ostinato starts, here realized by Perl on the gamba. The next section is underpinned by Santana on the lute. The division of continuo support is well-done. During this portion, however, I felt Sepec might have tried to play more with either dynamics or even some improvisatory fancies. The ending showcases a bit of what I’ve discussed above, the style of ornamentation at the end, the use of sequence, and the option for the musicians to guild the lily at the final cadence.

The ending here is nearly tongue-in-cheek (like the slide!) but doesn’t go out of its way to break new ground.

I listened again to the recording on Challenge Classics by Manze, Egarr, and Jacobs. The Manze reading shaves nearly an entire minute from the sonata, and for me the quicker pace at times was welcome. The continuo support from Egarr in this recording is far more sparse than the richer tapestry woven by Behringer, Perl, and Santana. Under Manze’s fingers the sonata takes on more virtuosity. What’s lost, perhaps, is the emotional gravitas which is amplified as we go from one musical idea to the other. Manze plays with some double stopping, too, which is interesting. While ornamentation is completely thrown away by Manze, I’m reminded of a former thought that sometimes when Manze encounters a slow section, he’s unsure of what to do with the music. What’s immediately different, to my ears, is that Manze does not engage in a lot of the “early Italian vocal style” ornamentation. His ending is nevertheless interesting, utilizing a unison double stop. This performance demonstrates for us, compared with Sepec’s, that the very simple, clean score we were left with requires significant contribution from the musicians to spin the music into something interesting, if not arresting to us as listeners. These two solutions don’t show one superior to the other, but instead help illustrate the possibilities for interpretation.

La Cest(a), op. 3

The opening of this work gives the violinist the opportunity to sing on the E string. Sepec uses the trillo here again, with repeating notes. The opening phrase opens with a great increase in dynamics and dramatic impact from the continuo. I dare say they may have taken inspiration from Letzbor.

The second section for me cooks, which shows me that Sepec is willing to exceed the musical speed limit, which is what I thought may have been missing in La Castella. In the slower section that follows, more sequences are presented, but there’s a lost opportunity here, perhaps, at varying the violin’s timbre. The smoothness that we get in the opening on the higher notes was a nice example of varied tone. Sepec does coax some variation out when he turns to push the instrument harder, which happens again in consort with the continuo group to end the sonata with a bang in full stylo concitato.

Enrico Onofri too recorded this sonata at the same overall timing, seven minutes. The opening is astonishing to me in the way Onofri controls the sound, using a very slow vibrato. His use of the trillo is in concert with Sepec’s. The continuo support in some cases is simpler than that from Sepec’s reading. The feeling in the fast section that follows pushes me harder to the edge of my seat; not only because of speed but in the way Onofri tailors his sound with trills. For the use of the “early Italian vocal techniques” Onfori is the boss. He clearly has more tricks up his sleeves than either Sepec or Manze. He commands out attention in the slower sequence that leads up to the finale; not through improvising against the notation, but by providing an almost never-ending cascade of different ornaments. His Imaginarium ensemble never quite get to the dynamic extremes of Il Rosario. However the ending? It’s well-done nevertheless.

La Bernabea, op. 4

This is one of my faves. At this point, we may start to think, was Pandolfi trying to portray some aspect of the musicians he named these sonatas after? Or were they favorites of the named personalities? We likely won’t know. But he’s not the only musician to name pieces after contemporary figures.

The recording by Letzbor and Ars Antiqua Austria is nearly two minutes longer than the recording by Sepec. The opening for me is deliberately made slower than it should be. The effect with the faster figures, when they come, is far more transparency to the falling violin line. The fourth section (track 4) is gruff and a bit wild in its finish, due in part to the contributions from his continuo team. This album for me was all about highlighting the contrasts in the music, to extremes that sometimes left me in want for more cohesion in the approach, contrasts be damned. In the slower sections, where Letzbor pulls even more time, were opportunities for improvisatory additions. Instead, the naturally slower notes like this are nearly difficult to get through, especially so with nothing happening in the continuo other than chordal support by an organ. The last two sections are just splendid, by comparison. I dare you not to tap your foot.

Il Rosario’s interpretation for me is superior, as is the sound quality from the recording. (The Letzbor pair of discs require additional amplification, perhaps they were going for a wider dynamic range?) The use of all three instruments in the continuo during the slower section in this sonata worked better for me than solo organ. The ending flourishes perhaps are not as shocking as they were under Letzbor, but again, it’s the balance across the entire sonata that works better for me. The decision to reduce dynamics in the last statement? Good call.

La Monella Romanesca, op. 4

Recordings by Martha Moore and Eva Saladin also have appeared after Manze’s; for another point of comparison I auditioned Moore’s reading of this sonata accompanied with just lute. The recording by Moore is simpler in conception, using just one continuo instrument. The sound of the recording, like that by Manze and Egarr (Harmonia Mundi) indicate a chamber setting, whereas the one by Il Rosario points to a church performance. The more colorful continuo I think is a benefit to Sepec’s playing. While Moore performs the overall sonata more quickly, I felt pace set by Sepec didn’t need any more fuel. I really appreciated his dynamic treatment of the section featuring the trills. The sparkle of Behringer’s harpsichord was really nice during this phrase.

Sepec retreats again in his sound before the sonata’s ending. The dynamic change and energy expelled during the final flourish reminded me again of Letzbor. Moore never turns up the heat enough to get to the same effect. The sound of his instrument really is exploited in this sonata, and it clearly is a special violin.

Saladin’s recording includes support from organ, which, like in the Letzbor, I think has a place. I’m less enchanted by her violin’s sound. I can’t speak to the natural balance between her violin and the organ, but to my ears, the organ is captured with great resolution, but the violin sound enjoys far less reverb and gets overshadowed by the organ sound. Her approach is less creative than Sepec’s, in terms of dynamics and accentuating changes in style and affect. The repeated notes that precede the sixteenth note runs lack the fire that Sepec brought to his performance. The runs themselves lose their virtuosic effect under Saladin’s fingers.

La Raimondo, Il Catalano

This recording includes four additional sonatas as part of Pandolfi’s “complete” oeuvre for violin sonatas. His style is immediately apparent to me. The excellent liner notes with this recording give us as much background on Pandolfi as we might hope to know; the notes do make mention of differences in the style of these four sonatas, which to my ears are less grandiose in conception, perhaps speaking to an earlier composition date? Or, the changes could be pragmatic. As the biographical details show, the man was on the move, having fled to France then ending up in Spain before his death. The taste and requirements in new locations may have dictated a change in compositional style.

La Raimondo is a confident work, I felt. Rhythm here commands our attention; the second phrase seems built upon the first, and sequences and repeated figures are not new to his style. The musical material continues with variation in a slightly faster section. The traversal to the violin’s higher gamut is once again the type of thing that would showcase the violinist’s ability to change positions on the E string, a type of “show-off” technique, that again, isn’t new in his writing.

For me the harmonic language in this short(er) sonata speaks to an evolution in style. The amount of material is actually sparse, given the number of repeats. The contributions from the continuo team help Sepec end the sonata in a built-up way consistent with his opp. 3-4 sonatas.

Il Catalano (named, for sure, after a Spaniard), is the longer of the four sonatas without opus numbers. The pace from the start I think is well-timed. Santana eventually disappears, handing over the continuo to Perl, who explores arpeggiated chords on the gamba. I liked this! Pandolfi plays with alternating melodic material, or with an almost martial theme that I found compositionally interesting. His technique at varying a sequential pattern pulls from the composer’s imagination in ways that likely break new ground; the rhetorical implications are well-spoken by Sepec.

The piece is clearly written by someone with an imagination and a good command for the violin. Il Rosario present this interesting work in vivid detail, highlighting for me the strong rhythmic component to its success.

Sound

Upon its own, you might find the sound from this recording to be pretty good; there is spaciousness between the continuo instruments, which aren’t quite in the same level of focus as the violin, which is to be expected. For my ears there is a slight thinness to the overall sound which is likely the flavor of the microphones used. The Manze recordings are notable as they use far less reverb. Compare the sound of this album with the Pandolfi recording by Martha Moore (violin) and Joris Loeff (theorbo). It may be a tad close, but the two instruments in this case, perhaps easier to capture, seem to be easier to hear in terms of detail and timbre.

The amount of reverb in Il Rosario’s recording required me to turn down the volume; it required more concentration to focus on the violin. It’s the one aspect of this recording that I’d wished had been tad better; it would have been glorious to get more detail from all four musicians.

Final Thoughts

Sepec is a violinist who hasn’t exclusively dedicated himself to period performance. My first listen to this recording revealed this to me, thinking that he didn’t feel as comfortable with some of the execution of the early Italian vocal gestures as, say, Onofri. I am still partial to the Harmonia Mundi recording by Egarr and Manze although for me it was not perfect in execution. Style wise, I am not sure any violinist can outshine Onofri for me. That said, Sepec and his companions that make up Il Rosario should be very proud of their resulting collaboration featuring Pandoli-Mealli’s music.

Of all the “complete” recordings of Pandolfi’s music, this one is likely the best all-around choice if you only wanted to purchase one. For one, it includes “bonus” sonatas in excess of the opp. 3-4 collections and it employs a colorful and well-coordinated continuo team to support the violin. Tempo-wise, Sepec pushes the speed in appropriate places to give us a good-measured thrill. In the slower sections, he’s often well-supported by the continuo.

While I saw opportunities for improvisation and more control of sound and dynamics, it’s not that Sepec is incapable of doing so. He does provide some interesting ornamentation and he does vary dynamics, which in turn, affects his instrument’s tone.

My biggest want from this release is to get closer to his instrument’s sound. There is enough resolution in the recording to convey its delicious timbre, but I felt I wanted to get just a little closer without the distraction from the reverb.

That said, Letzbor not included, many of the Pandolfi recordings are close-miked in deader spaces. This album’s use of a livelier acoustic sets it apart. And for that, overall, I think that was the right choice.

As mentioned, because Pandolfi’s music comes to us pretty bare, there is a lot of interpretive freedom in how it gets performed. With all the comparisons I made, I hoped to illustrate that not only are some interpreters more creative than others, but that beyond treatises on how to, say, ornament this music, there is no doubt in my mind that musicians are also listening to the recordings that come before theirs for inspiration. I found it difficult not to hear the echoes of Letzbor and Onfori specifically in this release. Which for me isn’t something bad.

Sepec and his colleagues manage to interpret these sonatas for themselves. This may be the best overall recording to date of Pandolfi’s violin sonatas, but that said, there are still joys to be found in other recordings as well. The contributions from Santana and Behringer for me stand out the clearest in having expert support in the continuo group. Beyond the talents of the violinists you may wish to compare, don’t forget the contributions and creativity of the continuo players. For me they contributed equally strongly as Sepec does on violin.