Générations - French Violin Music: A Convergence of Time and Talent

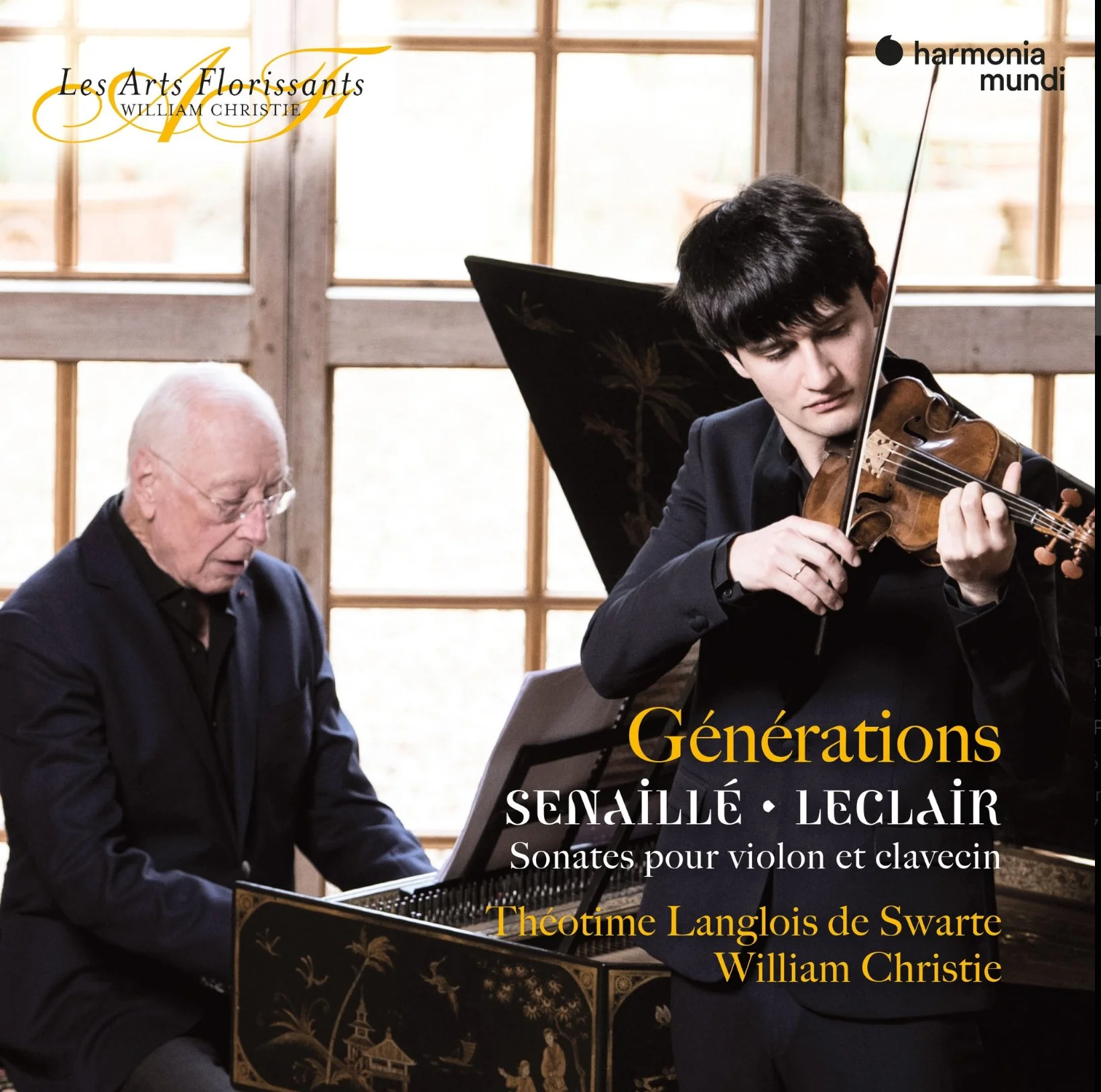

In the heart of a pandemic-altered world, "Générations" emerges as a testament to the timeless dialogue between past and present in French violin music. Recorded in the serene backdrop of William Christie’s home during the summer of 2020, violinist Théotime Langlois de Swarte and Christie himself on harpsichord delve into the rich tapestry of Jean-Baptiste Senaillé and Jean-Marie Leclair's compositions with an intimacy only afforded by limitless preparatory time.

Senaillé's world-premiere recording of op. 4 no. 5 in E minor is a highlight, with de Swarte's violin poignantly transitioning from naive bowing to a sorrowful weeping, beautifully accompanied by Christie's precise keyboard rhythms. The following G minor sonata by Senaillé features a violin that dances high without shrillness, enveloped in a distinctly French aura, suggesting a performance with a gamba might enhance its character.

The sonata in my favorite key of G minor was published 11 years earlier by Senaillé. The opening movement takes the violinist relatively high in its gamut, de Swarte does well not to sound shrill. The piece has a far stronger French whiff than the piece that preceded it. Harpsichord alone suffices but I think performing this with a single gamba might also be interesting. Each of the movements in this work is shorter in length; the second is labeled an Allemande but Christie and de Swarte take the tempo a little faster which works well. De Swarte sound comfortable with this piece, and the sound of his violin comes across well; it may not be the best violin I’ve heard, but it’s got its own sound which is quite rich.

Further into the album, Senaillé's D major sonata from his third book published in 1716 showcases a French baroque style deeply expressive with ornamental flourishes, while de Swarte's confident double stopping in the second movement subtly nods to Corelli's influence.

Leclair's op. 1 no. 5 adds contrast with its vigorous lower and higher violin dialogues, demonstrating his compositional prowess and echoing the high regard for his violinist skills.

In Senaillé’s start to his op. 1 no. 5 sonata, the harpsichord opens by itself, offering a dramatic, almost lamenting opening. The theme is then repeated with the violin leading the melodic aspect; de Swarte’s tone is dark and he achieves some intensity with a slight vibrato; he perhaps doesn’t fully exploit color but it’s a lean opening before Senaillé guilds the lilly with more intense writing with double-stopping. De Swarte doesn’t let up on the intensity. It’s moving. The corrente that follows is of course a binary dance and de Swarte and Christie don’t do a lot of differentiate themselves in the repeats.

Recorded in Christie's home, the sound is authentically captured—dry, close, and intimate, perfectly balancing the richness of the instruments. This recording not only highlights the craftsmanship of Senaillé and Leclair but serves as a reverent exploration of the emotional depth in early 18th-century Parisian violin music.